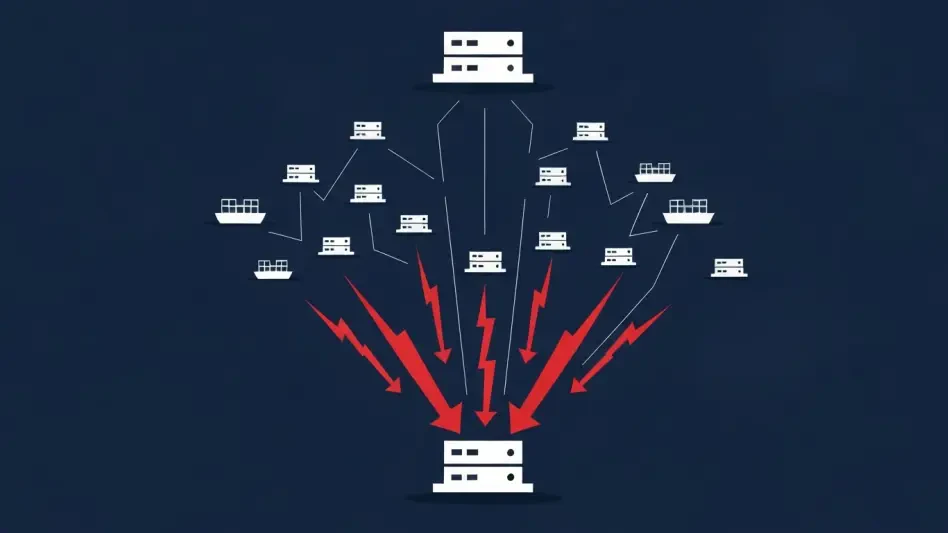

A new and sophisticated variant of the notorious Mirai botnet has been identified actively targeting the maritime logistics sector, exploiting vulnerabilities in digital video recorder (DVR) systems commonly used on commercial vessels. Cybersecurity researchers have uncovered this active campaign, dubbed ‘Broadside,’ which leverages a known security flaw to compromise devices, create a network of infected bots, and launch disruptive attacks. This development underscores the growing digital attack surface within the maritime industry, where interconnected operational and information technology systems create novel entry points for threat actors seeking to disrupt global supply chains or gain a strategic foothold within critical infrastructure. The campaign’s evolving infrastructure and advanced technical capabilities signal a significant threat that extends far beyond simple denial-of-service attacks.

1. Unpacking the Broadside Variant’s Advanced Capabilities

Unlike its predecessors, the Broadside variant demonstrates a notable evolution in the Mirai family, incorporating a custom command-and-control (C2) protocol and a unique ‘Magic Header’ signature to obscure its communications and evade detection by standard security solutions. Its technical design diverges significantly from typical Mirai builds by utilizing Netlink kernel sockets, a more advanced and stealthy method for monitoring system processes. This event-driven approach allows the malware to remain dormant and hidden, replacing the “noisy” and easily detectable filesystem polling techniques used by older variants. Furthermore, it employs payload polymorphism, a technique that subtly alters its code with each infection to prevent signature-based antivirus and intrusion detection systems from recognizing it. This combination of stealth, custom communication channels, and evasive maneuvers makes Broadside a far more resilient and formidable threat, capable of maintaining persistence on a compromised network without alerting system administrators to its presence.

The threat posed by this botnet extends well beyond its capacity for distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, as analysis has confirmed that Broadside actively attempts to harvest system credential files from compromised devices. This secondary objective indicates a more strategic, long-term goal of privilege escalation and lateral movement across the network. By stealing credentials, the attackers can transform a compromised DVR from a simple bot into a valuable strategic foothold. From this entry point, they can potentially move deeper into a vessel’s network, seeking access to more critical systems such as navigation, cargo management, or satellite communication controls. This capability for local account enumeration and privilege validation signals an intent not just to disrupt, but to infiltrate and potentially control key operational technology (OT) components, representing a severe escalation in the potential impact on maritime safety and security. This dual-purpose functionality marks a critical shift in the botnet’s operational playbook.

2. Attack Vectors and Defensive Postures

The primary attack vector for the Broadside campaign is a specific remote command injection vulnerability, tracked as CVE-2024-3721, found in TBK DVR devices. Threat actors exploit this flaw by sending a specially crafted HTTP POST request to the /device.rsp endpoint of the vulnerable device, allowing them to execute arbitrary commands and take full control. Once compromised, the device is co-opted into the botnet, ready to participate in high-rate UDP flooding attacks designed to overwhelm a target’s network infrastructure. The botnet also features a sophisticated “Judge, Jury, and Executioner” module, which actively scans for and terminates competing malware or processes on the infected device, ensuring its exclusive control. This territorial behavior, combined with fallback C2 communications over TCP port 6969 and a primary channel on TCP port 1026, demonstrates a robust and resilient architecture designed for sustained operations even if parts of its infrastructure are taken down.

Effectively mitigating the risk posed by Broadside and similar threats requires a multi-layered defensive strategy that goes beyond basic security measures. The first and most critical step is to ensure that all systems, particularly internet-facing devices like DVRs, are updated with the latest security patches to close known vulnerabilities like CVE-2024-3721. However, patching alone is insufficient. Organizations must implement robust network segmentation to isolate critical operational systems from the broader IT network, preventing an initial compromise on a less critical device from spreading to essential maritime controls. Deploying a comprehensive security stack, including a Network Detection and Response (NDR) or Extended Detection and Response (XDR) system alongside traditional firewalls and Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) solutions, provides the necessary visibility to detect and respond to anomalous activity. Proactive vulnerability scanning and disciplined patching hygiene are essential to shrink the window of opportunity for attackers who rely on slow update cycles.

3. Reviewing Strategic Defensive Protocols

The emergence of the Broadside botnet served as a stark reminder of the escalating cyber threats facing the maritime industry. This incident highlighted how seemingly peripheral IT equipment, such as a DVR, could be weaponized to create significant operational disruptions, potentially impacting a vessel’s primary communication and navigation systems through powerful DDoS attacks. The attackers’ focus on a specific, patched vulnerability underscored a critical lesson: the speed of patch deployment remains a decisive factor in cybersecurity readiness. The event also demonstrated the clear and present danger of converged IT/OT environments on vessels, where a single compromised device could provide a gateway for lateral movement into more sensitive control systems. The advanced, stealthy nature of the malware’s design confirmed that legacy security tools were no longer sufficient to protect modern, interconnected maritime assets. This campaign ultimately pushed the conversation beyond simple compliance, forcing a necessary reevaluation of proactive defense, network architecture, and incident response planning across the entire sector.