In the complex digital ecosystem where trust is a currency, the very tools designed to build and create can be twisted into weapons of espionage, turning a developer’s trusted companion into an unseen spy. A recent investigation has brought to light a sophisticated cyber espionage campaign where the popular source-code editor Notepad++ was compromised to serve as a distribution vector for a custom-built backdoor. Attributed to the Chinese advanced persistent threat (APT) group known as Lotus Blossom, this operation leverages a previously undocumented malware dubbed “Chrysalis.” This threat actor, with a history of operations dating back over a decade, has traditionally focused its efforts on government, telecommunications, and critical infrastructure entities in Southeast Asia. However, this latest campaign signals not only an expansion of their geographical targets into Central America but also a significant evolution in their technical tradecraft, showcasing a patient and persistent adversary capable of subverting widely used software to achieve its objectives.

A Deceptive Entry Through a Trusted Channel

Forensic analysis of the incident reveals an initial access vector that cleverly exploits the legitimate update mechanisms of Notepad++. The investigation established a clear chain of events where the standard execution of notepad++.exe and its associated updater, GUP.exe, was immediately followed by the launch of a suspicious process named update.exe. This malicious executable was not part of the legitimate software package but was instead downloaded from a remote server controlled by the attackers. The use of a Nullsoft Scriptable Install System (NSIS) installer for this update.exe file is a known tactic among Chinese APT groups, who favor its scripting capabilities for delivering initial-stage payloads. What set this particular installer apart was its custom runtime decryption mechanism, meticulously engineered to unpack its encrypted payload directly into memory. This in-memory execution is a deliberate evasion technique designed to circumvent traditional file-based antivirus scanning, which often fails to detect threats that never write their malicious components to the disk in a recognizable form.

Delving deeper into the payload delivery mechanism, the decryption routine stands out for its custom design, which consciously avoids standard cryptographic APIs that are frequently monitored by endpoint security solutions. Instead, the attackers implemented a stream-cipher-like algorithm built upon a linear congruential generator, a mathematical sequence that can produce pseudo-random numbers. The key material required for this process is derived from a previously calculated hash value, adding a layer of complexity that would frustrate automated analysis. The decryption routine systematically uses standard mathematical constants combined with several basic data transformation steps to recover the plaintext payload from its encrypted state. Once the payload is fully decrypted, it overwrites the original encrypted buffer in memory, and all temporary memory allocated for the decryption process is meticulously released to clean up any forensic artifacts. Finally, program execution is transferred to this newly decrypted code, which is then invoked with a set of predefined arguments that provide it with runtime context and resolved API information necessary for its next stage.

Unveiling the Chrysalis Espionage Tool

The payload, once successfully decrypted by a loader component identified as log.dll, is a custom and feature-rich backdoor that researchers have named “Chrysalis.” The extensive array of capabilities embedded within the malware indicates that it is a sophisticated and persistent espionage tool, far from a simple, disposable utility. To ensure its longevity and stealth on a compromised system, Chrysalis employs a series of advanced techniques. One of its primary evasion tactics is DLL sideloading, a method where the malware places a maliciously crafted DLL in the same directory as a legitimate, signed binary. When the legitimate application is launched, it inadvertently loads the malicious DLL instead of the intended one. To further blend in, this DLL is given a generic and innocuous name, such as log.dll, making detection based on filenames alone unreliable. The complexity is compounded by its heavy reliance on custom API hashing in both its loader and its main module, with each component utilizing its own distinct resolution logic to find and use system functions without leaving obvious traces.

The malware’s execution flow after being decrypted by log.dll involves several intricate steps designed to conceal its true purpose. First, a small piece of shellcode decrypts the main module using a hardcoded key and a simple but effective sequence of XOR, addition, and subtraction operations. Following decryption, the malware performs another round of dynamic import address table resolution to obtain a handle to Kernel32.dll and the GetProcAddress function, which are essential for resolving the addresses of other required Windows APIs. A significant effort was made to conceal critical strings, such as the names of targeted DLLs. These names are constructed on the fly using two separate subroutines that implement a custom, position-dependent character obfuscation scheme. In this scheme, each character is transformed through a combination of bit rotations and conditional XOR operations, ensuring that identical characters are encrypted into different values depending on their position within the string. This method effectively thwarts simple string-based signature detection, as the malicious indicators are never present in their plaintext form on disk.

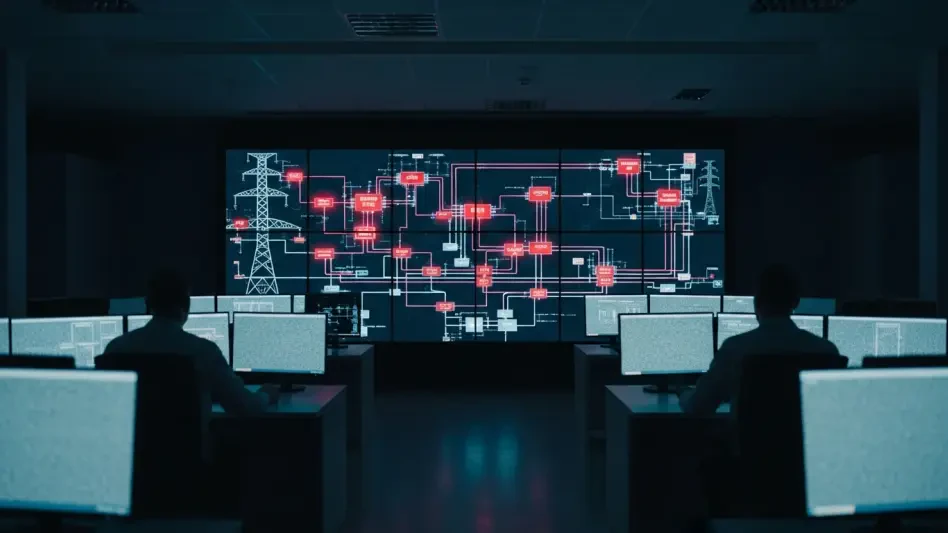

Command, Control, and Operational Intelligence

The main module of Chrysalis implements an even more sophisticated API hashing routine to further evade detection. Instead of relying on standard Windows loaders, the malware resolves functions by directly walking the Process Environment Block (PEB) and parsing module export tables, using only a target API hash. This custom routine applies a multi-stage arithmetic mixing algorithm inspired by MurmurHash, processing API names in four-byte blocks with rotation, multiplication, and final diffusion steps. This advanced technique makes static analysis and signature-based detection exceedingly difficult for security products to unravel. As a fallback, if this hashing process fails for any reason, the malware can still resolve APIs directly using the GetProcAddress function it obtained earlier. Once operational, the malware decrypts its internal configuration using the RC4 algorithm. This configuration reveals a single command-and-control (C2) endpoint hosted at api.skycloudcenter.com. The URL structure used for C2 communication deliberately mimics the style of DeepSeek chat API endpoints, a clever choice intended to camouflage malicious traffic within what appears to be legitimate web activity.

To complete its disguise, Chrysalis uses a generic module name and impersonates a standard Google Chrome browser user agent in its network communications. At the time of analysis, the C2 domain resolved to an IP address in Malaysia, and no other known malware samples were observed communicating with this infrastructure, suggesting it was dedicated to this specific campaign. The backdoor’s primary function is determined by the command-line arguments it receives upon execution. If no arguments are supplied, it proceeds to establish persistence on the infected host, primarily by creating a new service, with a registry-based method as a fallback. With the expected arguments present, the malware initiates its core functionality: gathering detailed information about the infected system and establishing communication with the C2 server to await commands. The malware performs several validation checks on responses from the C2 server before acting on any instructions, including verifying the HTTP status code and checking payload integrity. A small tag within the C2 response dictates the subsequent execution flow, which is handled by a switch statement with 16 possible cases, allowing for a wide range of remote commands and flexible control by the operators.

The Evolving Threat of a Persistent Actor

The discovery of the Chrysalis backdoor revealed a clear and concerning evolution in the capabilities of the Lotus Blossom APT group. While the threat actor continued to rely on established techniques like DLL sideloading and service-based persistence, its adoption of a multi-layered shellcode loader and advanced obfuscation methods signaled a strategic shift toward more resilient and stealthy tradecraft. This campaign also demonstrated a blended tooling approach, where the group combined its custom malware with widely available offensive security frameworks such as Metasploit and Cobalt Strike. Furthermore, their rapid operationalization of public research, particularly the abuse of a specific Microsoft component for sideloading, suggested that Lotus Blossom actively and continuously refines its operational playbook to evade modern security defenses. This aligns with previous intelligence, which detailed multiple cyber espionage campaigns by the group delivering other tools for post-compromise activities across various sectors. The consistent activity and evolving sophistication underscored the persistent and advanced threat posed by this group to organizations worldwide.